- Nostalgia Sleuth

- Posts

- The Day They Killed Optimus Prime

The Day They Killed Optimus Prime

How a Greedy Business Move Created the Saddest Scene of the 80s

I remember exactly where I was when Optimus Prime died. It was the summer of 1987, and I was in my cousin’s basement.

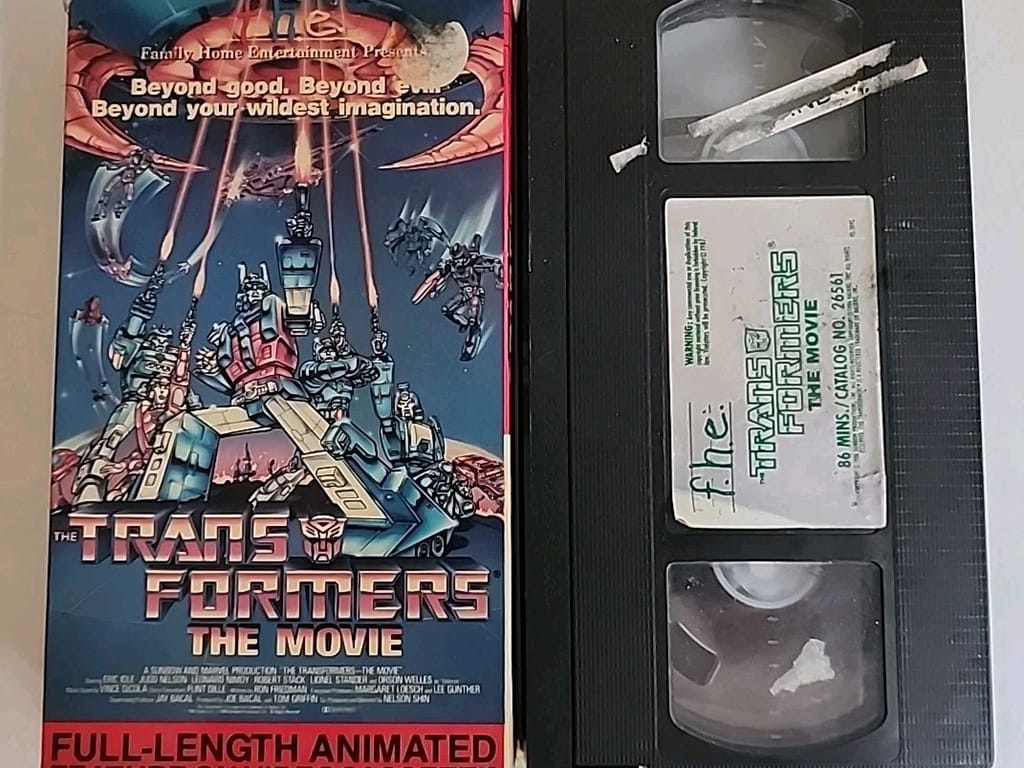

My aunt and uncle-in-law picked up a VHS copy of The Transformers: The Movie from our local rental store.

A rental store relic that scarred a generation in basements everywhere.

My cousin and I were diehard Transformers fans, sporting Optimus Prime and Bumblebee t-shirts, respectively, for this special occasion.

We weren’t expecting much. The Autobots always came out on top. Good guys don’t die in kids’ shows.

Boy, were we wrong.

About twenty minutes in, we watched our heroes executed one by one. Smoke billowed out of Prowl’s mouth as a gaping hole from a laser blast opened in his chest.

Ironhide begged for his life, wounded and defenseless, before Megatron shot him point-blank, dismissing his final plea: “Such heroic nonsense.”

Then came the coup de grâce.

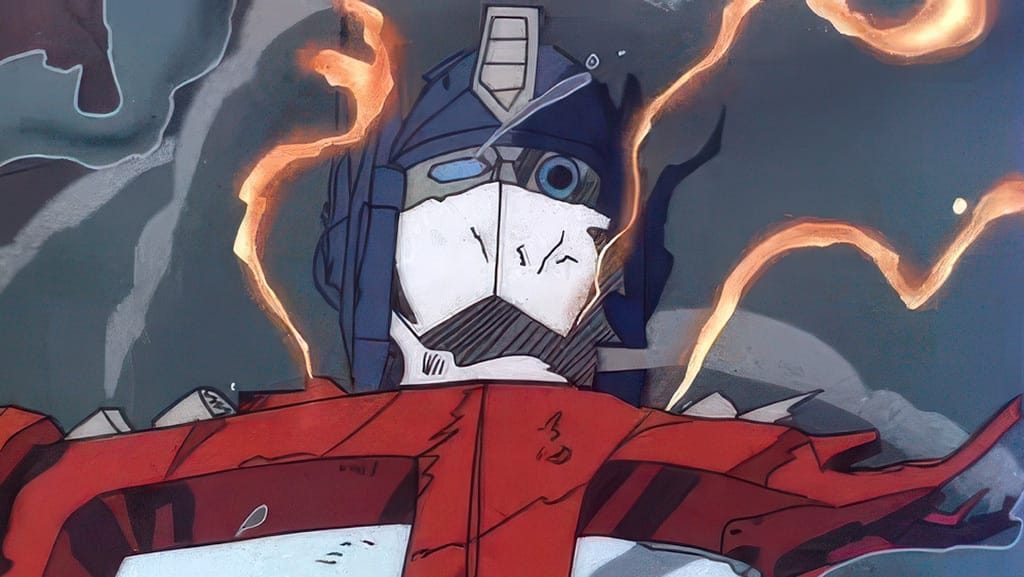

Optimus Prime, a father figure to a generation of kids, died on screen as Peter Cullen’s voice grew softer and weaker until there was… nothing.

Optimus Prime, cold and gray — a toy line’s sacrifice made real.

My cousin and I sat in stunned silence. After what felt like forever, my cousin burst into tears. And I soon followed.

What none of us knew at the time, especially the kids who saw the film in theaters, was that Prime’s death wasn’t driven by storytelling.

It was corporate strategy at its finest. Even at seven, I understood how capitalism worked.

As much as I enjoyed Saturday morning cartoons, my seven-year-old self would be quick to tell you they were glorified toy commercials.

Our favorite characters were at the mercy of ratings and toy sales. Still, it didn’t make Prime’s death any less shocking, a reality Hasbro would soon regret.

Saturday Morning Picks

Here’s your weekly lineup of retro merch and hidden gems. These are affiliate links. So, if you snag something, you’re helping support the sleuthing.

Latest Video

Latest video is live! Check out the newest deep dive on the channel.

Case of the Week

The Business Mandate

Travel back to 1986 when Hasbro turned emotional manipulation into an art form and called it product planning. The Transformers had become a multi-million-dollar franchise.

Seriously, you couldn’t go anywhere in the 80s without coming across the Autobots and Decepticons in one form or another, whether it was backpacks, Trapper Keepers, posters, or, of course, toys.

The original squad: the heroes they tried to kill off for shelf space.

Still, despite the unprecedented run, it was time for popular characters such as Optimus Prime, Ironhide, Jazz, and Prowl to make room for the new heroes Hot Rod, Kup, Blurr, and Ultra Magnus.

You would think Hasbro would do a grand sendoff special depicting our heroes riding off into the proverbial sunset.

Well, you would think wrong. Instead, Hasbro did what any dispassionate corporation would do: kill them all.

Years later, story consultant Flint Dille said, “We just thought we were killing off the old product line to replace it with new products.”

For Hasbro executives, these weren’t characters recognized and cherished by kids worldwide with fully formed personalities and backstories.

These characters were just expired inventory that happened to have legs.

Flint Dille, a story consultant who watched the toy massacre unfold and heard kids cry in the aisles.

The message was clear: kill off the 1984 roster to make room for more expensive toys.

I get capitalism. I really do. But someone should have told Hasbro that there’s a difference between discontinuing action figures and murdering beloved father figures.

The Creator’s Warning

Ron Friedman saw the disaster coming a mile away.

The seasoned screenwriter responsible for carrying out Hasbro’s execution order realized something that the executives overlooked: children form real relationships with fictional characters.

For kids, the Autobots weren’t toys. They were family. “To remove Optimus Prime, the physically remove Daddy from the family, that wasn’t going to work,” Friedman desperately warned the executives.

And he wasn’t wrong.

Ron Friedman, the writer who tried to save Prime and warned Hasbro they were killing Daddy.

As an only child growing up in a single-parent household, I looked to toys, comic books, and cartoons for characters to add to my family, and Transformers was no different.

While I didn’t see Optimus Prime as a father figure (that role was reserved for Splinter from Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles), I saw him as the cool uncle I could count on.

Whenever I had trouble at home or school, Optimus Prime was there to give me advice and remind me of how special I was.

Had I been in that boardroom meeting with Friedman, I would have shouted the same warning and shown the executives the error of their ways.

But that’s not how things turned out. Instead, Hasbro dismissed Friedman with corporate speak about “great things planned,” which is corporate for “We’re pivoting to synergy.” Or, more accurately, “more expensive toys.”

Still, Friedman wasn’t going to let Optimus Prime go out that way. He fought for Prime’s soul, creating the Matrix of Leadership.

This mythical container stored Prime’s essence and the wisdom of past Autobot leaders.

The Matrix of Leadership: Friedman’s last stand for Prime’s soul.

If Hasbro was going to make Friedman kill Prime, he was going to make it noble, a sacrifice instead of a cancellation.

But you can’t explain mythical succession to a seven-year-old watching one of their heroes turn gray and flatline.

The corporate machinery had spoken. The creative team saluted and loaded its narrative weapons. The massacre was scheduled for August 8, 1986.

The Backlash Earthquake

Theater owners were caught off guard. Kids weren’t racing out to buy the Hot Rod action figure or cheering for the new heroes.

Instead, they bawled their little eyes out, and many of them walked out mid-movie.

“The kids were crying in the theaters,” Dille recalled. “We heard about people leaving the movie. We were getting a lot of nasty notes about it. There was some kid who locked himself in his bedroom for two weeks.”

When a cartoon betrayal felt like losing a family member.

Parents wrote angry letters, demanding answers. How dare you kill our children’s hero?

Meanwhile, kids submitted tear-soaked notes, pleading, “Please bring Optimus Prime back.”

But poor box office wasn’t their only crisis. Even with a $6 million budget, the movie only made back $5.8 million domestically.

It opened in 990 theaters, landing 14th place due to much more audience-friendly competitors.

Hasbro ended up losing $10 million on their 1986 animated ventures, which ultimately killed the company’s theatrical ambitions, just as it did to Prime. However, things were just about to get worse.

The Resurrection Scramble

Panic surged through Hasbro’s corporate offices like a wave. The company planned to do the same thing for the G.I. Joe movie: kill Duke so Falcon could take over.

The reaction to Prime’s death changed everything. Last-minute orders flew to the animation studio: Duke lives.

The death scene remained, but hastily redubbed dialogue transformed the funeral scene into a “coma.” At the same time, an off-screen voice stated that Duke recovered.

If you go back and watch that scene, it’s obvious Duke is dead. Corporate cowardice saved him.

Duke was next until corporate panic changed his funeral to a ‘coma.’

For Transformers, it was too late. The damage was done. Prime was dead, filmed, and distributed. The letter campaign raged onward.

Sales plummeted as the new characters failed to fill the emotional gap left by the old guard.

It reminded me of something personal: the night my cousin’s dog destroyed my ALF toy during a sleepover.

I was devastated. The toy was my security blanket. I didn’t go anywhere without it.

My aunt offered to buy me a new one, but I declined. No new toy could replace the memories I made with ALF.

To her credit, my aunt wouldn’t give up. She was desperate to make amends with me.

So, she brought ALF to a seamstress who did a surprisingly good job stitching him back together.

But ALF was never the same. He didn’t look or feel like the friend I’d grown up with.

But unlike my ALF, Optimus Prime was Hasbro’s cash cow, and the company would try to resurrect the character in two horrifying parts.

First, there was the episode “Dark Awakening”. In the episode, the Quintessons reanimate Prime’s corpse, turning him into a zombie puppet to destroy his former allies.

When they turned Prime into a zombie puppet to sell more toys.

Toward the end, Prime briefly regains consciousness only to sacrifice himself again, steering an exploding ship into a Quintesson trap.

Instead of this being a triumphant return that many fans craved, it was a disgusting move that only served as proof of how far companies are willing to go for money.

On the second attempt, Hasbro brought Prime back, completely intact, in the episode “The Return of Optimus Prime”.

A Quintesson repaired Prime’s body so that he could fight a galactic “hate plague,” all while Stan Bush’s “The Touch” played in the background.

Hasbro’s do-over, resurrecting the hero they never should’ve killed.

While the second attempt was successful, the series had a stench to it. Death had become a revolving door, dramatically cheapening future stakes.

The Paradox of Failure

Here’s something Hasbro never saw coming: their massive mistake turned into something much more important than selling toys.

Prime’s death transformed him from a cartoon character to a cultural icon.

His sacrifice, even if it was heavily motivated by greed, gave him legendary status that his rivals didn’t have.

He-Man never died for his people, and Lion-O never made the ultimate sacrifice. They were comfortable in their toy commercial boxes.

The movie suffered tremendously before becoming a cult classic. Stunning animation paired with an epic soundtrack and mature themes helped achieve this new reputation.

The darkness that pushed children away in 1986 intrigued film students and nostalgic adults years later, instead.

Hasbro learned that emotional ties should never be compromised just because there is shelf space available in a store.

Other companies also learned from Hasbro’s blunder. We saw fewer character deaths in kids’ shows.

The Great Toy Massacre of 1986 was a business strategy that failed spectacularly.

But in its failure, it revealed the unpredictable, unquantifiable power of good storytelling over corporate calculation.

Sometimes, the most valuable thing you can give a character is a soul. Even if you have to kill them first.

Poll of the Day

P.S. Next week: Whatever happened to the California Raisins? How a Claymation ad campaign became chart-topping celebrities, and why it all crumbled.

Hit reply and tell me: what corporate betrayal from your childhood still stings?

First time reading? Check out previous issues in the archive.