- Nostalgia Sleuth

- Posts

- The $400 Million Raisin Heist

The $400 Million Raisin Heist

How dancing clay mascots became the perfect corporate crime

It’s Saturday morning in 1986, and you’re curled up on the couch in the living room with a bowl of Cookie Crisps.

Who am I kidding?

If your mom was anything like mine, you were either still in bed, dreading the household chores waiting for you, or you were watching the morning news, drudgingly eating Cheerios.

But, for the sake of this issue, we’ll live in the Good Place.

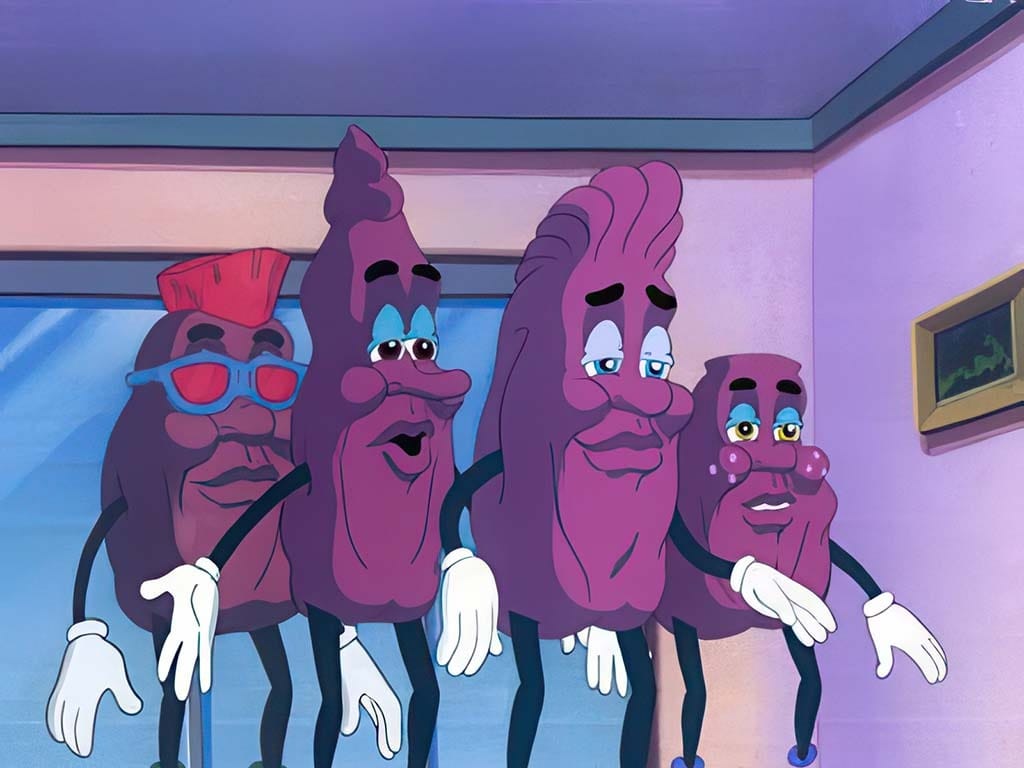

Anyway, you bite down on a spoonful of Cookie Crisps when a conga line of raisins, some sporting sunglasses, grooves across your screen as “I Heard It Through the Grapevine” blasts from your TV speakers.

Before you know it, you’re mesmerized by the little Claymation dancers who somehow have more swagger than most pop stars.

That was me.

I was that kid staring wide-eyed at the screen, mouth agape, milk dribbling down my chin.

Pretty sure most ‘80s kids were.

If we only knew that behind the viral craze that was the California Raisins was a massive $400 million business ($1.17 billion today) that chewed up and spat out everyone who gave birth to the mascots.

This is the story of a sunny California snack turned mob story, all set to a Motown beat.

A Word From Our Sponsor

Join over 4 million Americans who start their day with 1440 – your daily digest for unbiased, fact-centric news. From politics to sports, we cover it all by analyzing over 100 sources. Our concise, 5-minute read lands in your inbox each morning at no cost. Experience news without the noise; let 1440 help you make up your own mind. Sign up now and invite your friends and family to be part of the informed.

Saturday Morning Picks

Here’s your weekly lineup of retro merch and hidden gems. These are affiliate links. So, if you snag something, you’re helping support the sleuthing.

Case of the Week

The Setup: “A Stupid Idea” That Wasn’t So Stupid

Seth Werner was having a terrible day at Foote, Cone & Belding back in 1986.

At thirty-one years old, the copywriter found himself stuck with the California Raisin Advisory Board account.

It felt like a hazing ritual, and Werner was the pledge.

When friends asked what he was up to, Werner joked he’d probably “do something stupid like having a bunch of raisins dancing to ‘I Heard It Through the Grapevine.’”

Little did he know his throwaway line would become advertising gold.

Seth Werner, the copywriter at Foote, Cone & Belding whose self-deprecating joke about "something stupid like having raisins dance to 'I Heard It Through the Grapevine'" became advertising gold.

As you can imagine, the raisin industry was in shambles.

Sales were plummeting faster than New Coke’s popularity.

Kids like me saw raisins as the sad surprise at the bottom of Halloween bags.

Seriously, Mrs. Gerard, what did I ever do to you besides feed your Terror Dog, Zeus, whenever you weren’t home?!

Anyway, CALRAB desperately needed a miracle, and Werner’s “stupid idea” was their Hail Mary.

They handed Will Vinton’s stop-motion animation company $300,000 (about $840,000 today) for thirty seconds of Claymation magic.

But they also paid Buddy Miles, the legendary drummer who had worked with Jimi Hendrix, to lay down those soulful vocals that made the commercial feel like real music instead of just another jingle.

Buddy Miles, the legendary drummer and vocalist who provided the soulful R&B vocals that made the California Raisins feel like real musicians instead of just advertising jingles.

The commercial went live on September 14, 1986, and appeared on TV screens across the country.

The phones didn’t stop ringing, and raisin sales spiked 20% almost immediately.

Quick aside: what prompted this week’s issue was an old California Raisins stuffed toy I found while cleaning out my mother’s storage unit.

I forgot how obsessed I was with those mascots.

From the singing to the dancing to the charisma, the California Raisins had a hold on my generation.

This got me thinking about how much money the brand made over the years.

When I heard about that price tag for a single 30-second spot, I let out a whistle.

That rabbit hole led me to learn the Raisins brand raked in hundreds of millions during its peak.

Surely, everyone involved ate well, right?

A California Raisins plush toy, one of countless merchandise items that generated hundreds of millions in revenue that the creators never saw.

The Heist: How Success Became the Weapon

In just two years, the California Raisins went from a healthy snack to megastars.

They dropped four albums—two went platinum, selling over 2 million copies combined.

Their version of “I Heard It Through the Grapevine” actually hit #84 on the Billboard Hot 100.

These clay figures had legitimate Grammy nominations and even got cameos from the King of Pop himself, Michael Jackson, and The Genius Ray Charles.

When I say the California Raisins became a pop culture behemoth, I’m not joking.

Primetime specials, lunchboxes, t-shirts, a video game, toys—oh, boy, the toys.

The Smithsonian Institution thought the phenomenon was so culturally significant they added the merchandise to their permanent collection.

But you know who didn’t cash in?

CALRAB.

CALRAB was a non-profit state marketing commission.

By law, they couldn’t keep the money pouring in.

Every cent from t-shirts, records, and licensing went right back to the ad agency to create more content.

The California Raisins in their animated TV show form, where they transitioned from commercial mascots to legitimate entertainment characters with individual personalities.

Industry insiders called it a “vicious cycle.”

The bigger the Raisins got, the more CALRAB’s wallet hurt.

Meanwhile, just licensing “I Heard It Through the Grapevine” cost them $250,000 every single year.

At their peak, the marketing budget was twice that of actual raisin sales.

For every dollar of fruit sold, CALRAB spent two to keep the Raisins singing.

So, what do you do in this situation?

You created something that resonated with an entire generation but you’re going broke as a result.

Do you sell it? Let it die?

The California Raisins as a full band setup, complete with instruments and the "Top 10 Hits of the Week" chart that showed how they transcended advertising to become real entertainment.

The Victims: Three Stories of Corporate Betrayal

The Growers: These farmers paid steep fees to keep the show going, only to watch their product turn into a cash monster worth hundreds of millions while their paychecks shrank.

By July 31, 1994, they drew the line.

They staged a revolt, shutting CALRAB down for good, though the damage was done.

Will Vinton: The Claymation wizard behind the Raisins never got a dime of the licensing empire his work sparked.

Will Vinton, the "Father of Claymation" and Oscar-winning animator whose groundbreaking stop-motion clay animation brought the California Raisins to life and revolutionized advertising.

Even Michael Jackson loved Vinton’s work so much he agreed to appear in a Raisins commercial for free, but only if he could work directly with Vinton and bypass all the agency executives.

Vincent’s puppets should have generated a massive windfall for him and his family, yet his studio teetered on the edge of insolvency.

In 2002, Nike co-founder Phil Knight invested money to “save” the business, only to push Will out.

Knight’s son, Travis, gave the company a new name: Laika.

Today, they act like Will Vinton never existed.

Will Vinton surrounded by his Claymation creations, the animation genius who brought the Raisins to life but never secured a financial stake in the $400 million empire he created.

Us: We thought we were watching singing and dancing raisins.

What we really watched was intellectual property theft, dressed in nostalgia and sold with a smile.

The question is, “Where were the lawyers?”

Why weren’t contracts signed?

My heart goes out to Vinton because his family should be sitting pretty today.

It reminds me of the story of the creator of G.I. Joe selling the original toy for pennies compared to what the brand is worth now.

Maybe I’ll write about that one day.

The California Raisins performing on stage during their peak popularity, when they were legitimate recording artists with platinum albums and Grammy nominations.

The Perfect Crime: Legal, Profitable, Invisible

The theft looked squeaky clean on paper.

FCB made sure every number—album sales, merch revenue, TV ratings—worked in its favor while leaving its clients broke.

The farmers footed the bills while the agency scooped up the profits.

Vinton provided the talent but owned nothing.

When the whole thing finally collapsed, the agency walked away with more money than most companies earn in a lifetime, while the growers lost their farms and Vinton lost his life’s work.

The California Raisins showed big companies how to take advantage of the little guys while pretending to spread a little magic.

Two California Raisins ice skating during a live performance, showcasing how the characters transcended commercials to become full entertainment spectacles.

The Grapevine Never Lies

Whenever you spot the California Raisins in a meme or an old TV ad, remember you’re staring at proof of one of the slickest marketing heists ever pulled off.

What started as a goofy gimmick blossomed into a pop-culture smash and showed how companies cashed in on the folks who made it a hit.

The raisins may have stopped dancing, but the music never stopped playing.

You just have to know how to listen.

So next time someone swears childhood shows were harmless fun, pause and wonder: Who walked away with the money?

And what other fan-favorite mascots are hiding similar secrets?

Poll of the Week

P.S. Next week I’m diving into the making of “Eerie, Indiana”, the Twilight Zone for 90s kids.

Join me as I untangle the oddball series NBC buried before it could become a classic.

And reply to share the childhood mystery you’d like me to dig into next.

First time reading? Check out previous issues in the archive.